THE MUDDLE FAMILIESTHE LINEAGE & HISTORY OF THE MUDDLE FAMILIES OF THE WORLD INCLUDING VARIANTS MUDDEL, MUDDELL, MUDLE & MODDLE |

||||

|

[Home] [Origins] [Early Records] [General Notes] [Master Index] [Contact me]

The Clockmakers of Rotherfield

What might well be the first mention of a clock in Sussex was in the will of William Alchorne, who was a blacksmith at Rotherfield. William had made his will on 19 March 1580, a few weeks before his death, and in this will he states that My will is that my clock in my shop shall stand and continue there forever.[1] Nothing more is known about this clock so we don’t know what sort of clock it was or who had made it, but as William was a blacksmith and it is known that blacksmiths did try their hand at making clocks it seems quite likely that William had made this clock. The place where William lived and had his blacksmith’s forge was probably the ancient property now called Town Hill House that stands across the road from Rotherfield Parish Church. This property passed from William to his son Anthony, then to Anthony’s son Philip, then to Philip’s son Philip Alchorne. It seems that the house was then divided into two and separated from the workshop and forge. In 1649 the north-east section of this house was sold to Robert Dadswell and on Robert’s death in 1676 it was inherited by his son Edward Dadswell, who was a yeoman farmer at Rotherfield. Then in 1680 Edward Dadswell sold it to Thomas Muddle, who was a blacksmith and worked at adjacent forge now owned by Abraham Alchorne, and where William Alchorne had once set up his clock. There exists a lantern clock finely inscribed on the dial ‘Tho Muddle Rotherfield’ that also has a rather crudely executed inscription ‘1685 W H’ above the dial, which is thought to have been made by this Thomas Muddle, born 1641 died 1688. This clock was probably purchased by fellow blacksmith Thomas Hoadley, who had his forge in the Boarshead area of Rotherfield Parish, and it was Thomas Hoadley who added the inscription ‘1685 W H’ to commemorate the birth of his son William Hoadley, who was later to become a clockmaker. So it seems that a century after William Alchorne had set up and possibly made his clock the same forge was now being used by Thomas Muddle to again make clocks. On the death of Thomas Muddle in 1688 clock making at Rotherfield passed to his son Thomas, who, though only 16 years old when his father died, ended up working at the same forge and making clocks there. The second wife of this Thomas was Mary Dadswell, who was the daughter of the Edward Dadswell, who had sold the house on Town Hill to the father of this Thomas back in 1680. It’s thought that this second Thomas Muddle, born 1671 died 1756, probably passed on his clock making skills to the other two Rotherfield families that became clockmakers, by taking as apprentices William Hoadley, whose birth had been commemorated by the clock made by the first Thomas Muddle, and Thomas Dadswell, who was his wife’s brother. This second Thomas Muddle had three sons and he passed on his clock making skills to all of them. His eldest son, yet another Thomas Muddle, born 1707 died 1785, became a clockmaker at Tunbridge Wells. His second son, Edward Muddle, born 1709 died 1788, became a clockmaker at Chatham. His third son, Nicholas Muddle, born 1716 died 1807, became a clockmaker at Lindfield and then Tonbridge. And it was with the death of Nicholas that clock making died out in the Muddle family as none of the next generation took up this occupation. Clock making in Dadswell family started with Thomas Dadswell, born 1688 died 1752, who was probably an apprentice of his brother-in-law Thomas Muddle, clockmaker at Rotherfield. After completing his apprenticeship, probably in 1709, when he was 21, he set up his own clock making business at Burwash where he was recorded as taking his nephew Thomas Dadswell, son of his brother Edward, as an apprentice in 1735, and it’s thought that he also took his nephew John Dadswell, son of his brother Alexander, as an apprentice in about 1740. This nephew, John Dadswell, born 1727 died 1789, took over his uncle’s clock making business at Burwash after his uncle’s death in 1752 and continued as a clockmaker there until his own death in 1789. Thomas Dadswell, born 1719 died 1769, who had been an apprentice to his uncle Thomas Dadswell, clockmaker at Burwash, then became a clockmaker at Rotherfield from about 1742 and then at East Grinstead from about 1757. Thomas would have been passing on his clock making skills to his two eldest sons, Thomas and Edward, when he died in 1769. His eldest son, Thomas Dadswell born 1749 died 1794, probably then took over the clock making business at East Grinstead and may have continued the training of his younger brother Edward. This Thomas continued to work as a clockmaker at East Grinstead until his death in 1794. The other son, Edward Dadswell, born 1754 died 1802, may have completed his apprenticeship working for his elder brother at East Grinstead but it seems more likely he completed his apprenticeship working for his father’s cousin John Dadswell at Burwash, and then in about 1783 he set up his own clock making business at Eastbourne until his death in 1802 brought to an end the Dadswell family’s association with clock making. Clock making in the Hoadley family started with William Hoadley, born 1686 died 1756, who was probably an apprentice to Thomas Muddle, born 1671 died 1756, clockmaker at Rotherfield and the son of the Thomas Muddle who is thought to have made the lantern clock that commemorated William’s birth. William became a clockmaker at Rotherfield and passed on his clock making skills to his only son, William Hoadley, born 1729 died 1763, who married Sarah Dadswell, the sister of Thomas Dadswell, born 1719 died 1769, who was a clockmaker at Rotherfield and then East Grinstead. This second William Hoadley had two sons, but they are not thought to have become clockmakers as they were only very young children when William died prematurely from smallpox and brought to an end the Hoadley family’s connection with clock making. The above is an outline of the three clock making families that originated in Rotherfield and how they were interconnected by both family and occupation ties. What follows is a detailed history of each of the clockmakers in these families together with blacksmith Thomas Hoadley and yeoman Edward Dadswell as their lives have connections with the clockmakers. A later clockmaker in Rotherfield, who was unconnected to the above families, was William Damper, born 1785 died 1865. He was principally a farmer at Rotherfield but had a sideline in making clocks, which became his main occupation after he retired from farming and moved to Tunbridge Wells. Full details of his life are at the end of this article. It has not been possible to establish what, if any, connection there is between this William Damper and the William Damper who was born at Pembury in 1811 and had a clockmaking business at Calverley Road in Tunbridge Wells. This William had a son, also called William Damper, and grandsons, William George Damper and Albert James Damper, who were all clockmakers at Tunbridge Wells.

Thomas Muddle (1641-1688) blacksmith and clockmaker at Rotherfield

Thomas Muddle was the eldest son of Rotherfield blacksmith John Muddle and his wife Sarah Luxford; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex, and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 5 September 1641. In 1648, when he was 7 years old, his father died, then when he was 23 years old Thomas married Mary Baker at St Michael's Church in Lewes, Sussex on 25 August 1664. (Mary's surname was spelt Backer in the marriage register and is assumed to be a misspelling of Baker rather than Barker as Mary makes bequests to Henry and Edward Baker in her will.) Thomas and Mary lived at Jarvis Brook in Rotherfield Parish where they had six children born between 1664 and 1677, the eldest dying while still a young baby. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 7 December 1671 Thomas, described as 'Thomas Muddle junior' was presented as the heir to 'Thomas Muddle senior' his grandfather, as Thomas junior's father John Muddle, who was Thomas senior's only son, had predeceased Thomas senior. Therefore Thomas was admitted as tenant of his grandfather's property described as two cottages, a barn and 8 acres of assert laying at Maynard's Gate, held by a yearly rent of 2s.[2] When Thomas died in 1688 the description of this property had reverted to its earlier description of a cottage, a barn and 6 acres of assert laying at Maynard's Gate, held by a yearly rent of 2s. At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 9 March 1679, 13 April 1680, and 12 January 1681 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[3] Also at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 12 January 1681 it was recorded that out of court on 10 September 1680 Edward Dadswell, only son and heir of Robert Dadswell, sold to Thomas Muddle several pieces of assert in Rotherfield containing 5 acres with a messuage and barn built on them, and also a messuage and garden upon Townhill in Rotherfield that was formally the northeast end of Philip Alchorne's house and held by a yearly rent of 3d. Thomas was admitted to the 5 acres with messuage and barn on payment of a fine of £3 and to the messuage and garden on Townhill on payment of a fine of 20s to the Lord of the Manor.[4] At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 6 June 1681 and 15 July 1681 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[5] Thomas was a churchwarden at Rotherfield in 1684; he was one of the two churchwardens that signed the Bishop's Transcripts for that year. At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 12 March 1685 and 28 April 1686 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[6] Thomas was almost certainly a blacksmith, because at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 28 April 1686 he was described as being the occupant of a messuage, smith's forge, garden and backside enclosure upon Townhill in Rotherfield, when out of court on 27 April 1685 Abraham Alchorne sold this property to John Heaseman and his heirs.[7] There exists a lantern clock finely inscribed on the dial 'Tho Muddle Rotherfield' and rather crudely inscribed '1685 W H' above the dial, that is thought to have been made by Thomas for fellow Rotherfield blacksmith Thomas Hoadley, who had his forge in the Boarshead area of Rotherfield Parish, and that it was Thomas Hoadley who added the crude '1685 W H' inscription to commemorate the birth of his youngest son, William Hoadley. This is the only evidence that Thomas made clocks, but it was fairly common for blacksmiths of this period to become clockmakers. This William Hoadley was later to become a Rotherfield clockmaker, possibly after being an apprentice to Thomas' son, another Thomas Muddle, who was himself a Rotherfield clockmaker.

At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 25 May 1687 and 3 August 1687 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[8] Five months after Thomas last served as one of the homage at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield he died at the age of 46, and was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 26 January 1688. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 1 March 1688 the death was recorded of Thomas Muddle, who held a cottage, garden and two pieces of assert of Smallgrove containing 6 acres lying near Maynard's Gate held by rent of 2s and other services, also a separate piece of customary land in Rotherfield containing 5 acres with a messuage and barn built on them held by rent of 15d and other services, and also a messuage and garden upon Townhill in Rotherfield that was formally the northeast end of Philip Alchorne's house and afterwards Dadswell's and held by a yearly rent of 3d and other services. For a Heriot a cow valued at 40s was seized for the Lord of the Manor. The heir to these properties was Thomas Muddle junior, who was admitted as tenant of these properties on paying reliefs to the Lord of the Manor of 2s, 15d and 3d respectively for the three properties. As he was under age, being only 16 years old, guardianship of Thomas and his properties until he attained the age of 21, was granted to his grandfather's cousin Thomas Muddle, a yeoman of Mayfield, and the closest living male relative of Thomas junior.[9] When Thomas died he owned the three properties detailed above but not the smith's forge where he worked. Thomas died intestate, and administration of his estate, the personal estate part of which was valued at £428 9s 2d, then a considerable sum, was granted to his widow Mary, by the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 27 April 1688.[10] Eight months after her husband's death Mary used some of the money that he had left her to give a 100 year mortgage of £200 at 4½% to John Elliott, yeoman of Rotherfield, on his properties called Westlands, Grigges and Robins in Chiltington and Westmeston in Sussex. The mortgage was dated 13 September 1688 and interest of £4 10s was to be paid every six months on 14 March and 14 September. The mortgage continued for eleven years until John Elliott sold this property to John Vinall, yeoman of Chailey in Sussex, on 27 September 1699 when William Vinall, yeoman of Chailey, paid Mary £215, being the principal money and outstanding interest.[11] Seventeen years after her husband's death Mary died and was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 16 April 1705. Mary's will, dated the 5 March 1705 and proved at the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 21 April 1705, made the following bequests: £10 to be spent on her funeral and £3 to go to the poor of Rotherfield parish; to her daughter Elizabeth Banks £10; to her grandchildren Sarah, Mary and Elizabeth Bunyer [Bunyard?], from the first marriage of her daughter Elizabeth Banks, £10 each; to grandchild Rebecca Banks, from the second marriage of her daughter Elizabeth Banks, £5; to son Thomas Muddle £40 and half of the residue of her personal estate; to daughter Mary Muddle £40, all household goods, and half of the residue of her personal estate; to daughter Sarah Muddle £50; to sister [actually sister-in-law] Mary Muddle £3; to Henry and Edward Baker of Rotherfield £1 each. She made her son Thomas and daughter Mary joint executors.[12]

Thomas Muddle (1671-1756) clockmaker and whitesmith at Rotherfield

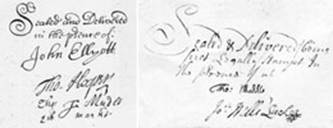

Thomas Muddle was the only surviving son of Rotherfield blacksmith and clockmaker Thomas Muddle and his wife Mary Baker; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex, and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 13 June 1671. When Thomas was 16 years old his father died during January 1688 and as the only surviving son Thomas inherited his father's properties. So at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 1 March 1688 when the death was recorded of Thomas Muddle senior, who held a cottage, garden and two pieces of assert of Smallgrove containing 6 acres lying near Maynard's Gate held by rent of 2s and other services, also a separate piece of customary land in Rotherfield containing 5 acres with a messuage and barn built on them held by rent of 15d and other services, and also a messuage and garden upon Townhill in Rotherfield that was formally the northeast end of Philip Alchorne's house and afterwards Dadswell's and held by a yearly rent of 3d and other services. Thomas being the heir was admitted as tenant of these properties on paying reliefs to the Lord of the Manor of 2s, 15d and 3d respectively for the three properties. As he was under age guardianship of Thomas and his properties until he attained the age of 21, was granted to his grandfather's cousin Thomas Muddle, a yeoman of Mayfield, and the closest living male relative of Thomas.[13] Then later that year on 13 September 1688 Thomas was one of the witnesses when his mother gave a mortgage to John Elliott, and this showed that he couldn't then sign his name but only make his mark of a J, but later he was able to engrave his name on the clocks he made and when he witnessed the marriage settlement of his niece Sarah Rose on 3 July 1731 he was able to sign his name Tho: Muddle, so he must have received some education after his father's death.

When his father died Thomas had probably been learning the trade of clocksmith from him, but he would have then been far from fully trained in the craft, so was he from then on self-taught or did he complete his apprenticeship with another master clockmaker though no record of this has been found? However he learnt his trade it seems likely that by about 1692 Thomas had set himself up in business at Rotherfield as a master clockmaker. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 28 July 1691 Thomas Muddle was one of many on a list of customary tenants of the manor that were in default and each one in mercy (fined) 6d. One of the obligations of customary tenants was to attend court and if they didn't they were liable to an amercement, effectively a fine, and put on a list for the beadle to go round and collect the amercement.[14] At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 16 June 1698 and 6 November 1699 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[15] When he was 31 years old Thomas married 36-year-old Elizabeth Maynard, who was from Brenchley in Kent, at the Parish Church of St Peter & St Paul in Tonbridge, Kent on 9 September 1702 by licence. Elizabeth was the daughter of Richard Maynard and Anne Parker and she had been baptised at the Parish Church of All Saints in Brenchley on 28 December 1665. Thomas and Elizabeth didn't have any children. Elizabeth died just on a year after their marriage, at the age of 37, and was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 4 September 1703. When his mother died in April 1705 Thomas inherited £40 and half of the residue of her estate, and he was also a joint executor with his sister Mary of his mother’s will. Twenty-one months after the death of his first wife and two months after his inheritance from his mother, Thomas, at the age of 34, married 27-year-old Mary Dadswell at the Parish Church of St Michael & All Angels in Withyham, Sussex on 26 June 1705 by licence. The marriage record states that both Thomas and Mary were from Rotherfield. Mary was the daughter of Edward and Elizabeth Dadswell; she had been born at Rotherfield and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 17 April 1678. Thomas and Mary lived at Rotherfield where they had seven children born between 1707 and 1718, the third of these children, who was their eldest daughter, died in 1713 when only two years old.

Thomas was the person referred to by Britten in his standard work on former clock and watch makers, in which he gives Thomas Muddle, Rotherfield, as a maker of lantern clocks, 1700-1710. Robert Dadswell, a brother of Thomas' wife, in his will of 1710 referred to Thomas as a clocksmith of Rotherfield when he made Thomas one of the overseers of his will.[16] Catherine Pullein in her history of Rotherfield quotes a letter from Mr Herbert F Fritt of Jarvis Brook, in which he states that he has a grandfather clock by Thomas Muddle which had the inscription 'July ye 6th, 1712, this clock was set up'. Fritt also had a clock by 'Thos. Muddle, Tunbridge Wells' which he dated to about 1715, but this date is at least 20 years too early as this clock would have been made by Thomas the son of this Thomas sometime after 1739. The 15 June 1858 edition of The Sussex Advertiser reported that one of the household items of the late Miss Elizabeth Tompsett of Ticehurst to be sold by action on 22 June 1858 was an 8-day clock in wainscot case, inscribed T Muddle, Rotherfield. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 20 July 1709 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage, and at this court he was also nominated to the office of Beadle for the following year. Thomas remained in the office of Beadle for eight years, attending the following courts as Beadle; 12 July 1710, 2 July 1711, 3 June 1712, 8 June 1713, 22 Apr 1715, 6 Apr 1716, 6 Nov 1716 and 9 May 1717.[17] At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 9 May 1717 it was recorded that clocksmith Thomas Muddle had given three mortgages. The first of £105 was to John Elliott for his property consisting of messuage, barn, garden and 10 acres of assert at Crowborough with a piece of assert called the Hop Garden at The Mead containing 3 acres. The second also of £105 was to Robert Bridger for his property consisting of a cottage and two crofts of assert of Anthony's Reed with another croft called Sheep Coates and another piece called Harrises Field containing 35 acres. The third was out of court on 16 July 1716 in the presence of his Deputy Beadle, Thomas Dadswell, for £27 10s to Nicholas and William Hills for their property consisting of a parcel of land called Gamon's Croft containing 5 acres in the occupation of Nicholas Hills and held by rent of 11d.[18] Then at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 2 April 1719 William Hills sold to whitesmith Thomas Muddle, a parcel of land called Gamon's Croft containing 4 acres abutting the land of Thomas Muddle on the north, the highroad on the south, and land of Thomas Bot on the east, and now in the tenure of Thomas Muddle. And the first proclamation was made for Thomas Muddle to come to court to be admitted.[19] At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 22 April 1720 Thomas Muddle attended the court as Deputy to Beadle Andrew Jenkins. At this court clocksmith Thomas Muddle gave another mortgage to John Elliott on his property consisting of messuage, barn, garden and 10 acres of assert at Crowborough with a piece of assert called the Hop Garden at The Mead containing 3 acres, this time John Elliott was to repay £147 on 28 April 1721, he had presumably already repaid the earlier mortgage of £105. Also at this court on the second proclamation Thomas Muddle was admitted as tenant of the property he had earlier purchased from William Hills, on payment of a fine of 50s to the Lord of the Manor. At a Special Court of the Manor of Rotherfield also held on 22 April 1720 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage.[20]

At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 23 April 1721 Thomas Muddle attended the court as Deputy to Beadle Andrew Jenkins. Then at the courts held on 29 March 1722 and 18 April 1723 Thomas Muddle was sworn in as one of the homage.[21] Thomas Muddle was described in the manorial records sometimes as a clocksmith and sometimes as a whitesmith. A whitesmith is normally thought of as a worker in tin and other non-ferrous metals, so these records seem to indicate that Thomas probably made many other items in non-ferrous metals, not just clocks, though as clocks were the only items that were inscribed with the maker's name they are the only items that can be identified as being made by Thomas.

It was possibly around 1700 that Thomas started taking on apprentices as he probably trained the William Hoadley whose birth is thought to be commemorated by the clock made by his father that was inscribed 'Tho Muddle Rotherfield' and '1685 W H', this William Hoadley being 14 years old in about 1700, which was the normal age to start a 7 year apprenticeship. This William Hoadley later became a clockmaker at Rotherfield, describing himself as this in his 1755 will. Another person Thomas is thought to have taken as an apprentice was his wife's brother, Thomas Dadswell, who would have been 14 years old in 1702, and who later became a clocksmith at Burwash. As well as these two possible apprentices Thomas also trained his three sons as clockmakers; son Thomas, the eldest, became a clockmaker at Tunbridge Wells, son Edward a clockmaker at Chatham, and son Nicholas a clockmaker at Lindfield and then Tonbridge. Nicholas the youngest of these sons would have probably completed his apprenticeship in 1737 when he would have been 21 years old and it was probably around this time that the three sons start moving away from Rotherfield and setting up their own businesses, the eldest son, Thomas, is known to have been at Tunbridge Well with his own business by 1739. All clocks inscribed 'Thomas Muddle of Tunbridge Wells' being made by this son, while clocks inscribed 'Thomas Muddle of Rotherfield' were made by Thomas, the subject of this section, except possibly the very early ones, pre-1688, that would have been made by his father Thomas. On 3 July 1731 Thomas was one of the witnesses to the marriage settlement between his niece Sarah Rose and her intended husband Henry Hall.

Thomas died on 22 March 1756, at the age of 84, and was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 27 March 1756; the burial record describing him as a clocksmith. Thomas had made his will on 18 March 1748, eight years before his death, when he described himself as a whitesmith of Rotherfield, and this will was proved by the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 23 March 1756. In this will Thomas made the following bequests: to wife Mary £10; to son Edward £10; to daughter Ann wife of William Foreman £10; to daughter Elizabeth £10; to son Nicholas £10; to daughter Sarah £10; to son Thomas, who was sole executor, all the residue of his personal estate.[22] Nine months after the death of her husband Mary died on 23 December 1756, at the age of 78, and was buried with her husband in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 27 December 1756. Thomas and Mary's grave is marked by an inscribed headstone.

Thomas Muddle (1707-1785) clockmaker at Tunbridge Wells

Thomas Muddle was the eldest of the three sons of Rotherfield clockmaker and whitesmith Thomas Muddle and his wife Mary Dadswell; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex, and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 1 September 1707. Thomas would have been trained as a clockmaker by his father, who was a master clocksmith and whitesmith at Rotherfield, and though he probably completed his apprenticeship in 1728 at the normal age of 21, it seems likely he continued working with his father at Rotherfield for about the next ten years while his two younger brothers were being trained as clockmakers. It was in early 1739, when he was 31 years old, that Thomas was first recorded as being a master clockmaker at Tunbridge Wells in Kent. He was recorded in a Private Act of Parliament of 21 November 1739 that confirmed an agreement between Maurice Conyers, Lord of the Manor of Rusthall, and the freehold tenants of that manor, which released the Lord of the Manor from any responsibility in relation to these freehold tenements. All these freehold tenements were described in detail and the one relating to Thomas was as follows:[23] And also all that Messuage or Shop near adjoining the other Side of the fore-mentioned Road [to the Chapel Bridge], being the most Eastern of the Tenements on the North Side of the said Passage [leading from the Walks to the Chapel], now in the Tenure or Occupation of Thomas Muddle, containing in Front next the said Passage to the Chapel Thirteen Feet, and in Depth on the West Side next the Road Eight Feet, and in Breath at the North End Four Feet Six Inches, and in Length from North to South on the East Side Eleven Feet, as the same is now particularly described in the Plan hereunto annexed, and which said Messuage is described in the said Lot marked (C), by the Name or Description of Muddle. This is a description of Thomas’ shop in a prime corner site in Tunbridge Wells, the Walks being the old name for the Pantiles and Chapel Bridge Road being the modern Nevill Road with the Passage being the walkway joining the two. There is an error in the description in that the Chapel Bridge Road would have been on the east side of the tenement not the west, but allowing for this means that Thomas’ shop was where the main entrance to Barclays Bank now stands, and it would have been passed by all the gentry visiting the spa town of Tunbridge Wells to take the waters at the height of its popularity. Unfortunately the map that would have confirmed the location of Thomas’ shop and shown its surrounding buildings has not survived. The above was the location of Thomas’ shop but it was not where he lived, other records show that he lived at Southborough in Tonbridge Parish, about 2½ miles to the north of his shop. The Tonbridge Overseers’ Accounts and Poor Law Assessments record Thomas Muddle being assessed from 1739 to 1775 on what was initially called a ‘new house’ in the East Division of Southborough that had a rental value of £1 10s on which he was assessed for yearly payments for the Poor Law that varied between 2s and 10s 6d. Then in 1776 Thomas Cranwell was assessed for the same house described as late Muddles.[24] This was almost certainly a freehold property that Thomas owned from 1739 to 1775 as there are no records in the Court Books of Southborough Manor of Thomas buying or selling copyhold property, but he is on the 13 October 1740 list of all inhabitants, not just copyhold tenants, of Southborough Manor.[25]

While living at Southborough Thomas was recorded in the Vestry Accounts of King Charles the Martyr Chapel in Tunbridge Wells, which was just across the road from his shop, as Mr Muddle receiving payments for work done. The first entry was in 1743 when he was paid £11 9s 7d that is thought to be for a major repair of the clock, which had been made for the church in about 1685 by Edmund Massey of London. Then for the next 16 years, from 1744 to 1759, Thomas was paid 10s each year for looking after the clock, with an extra 5s in 1752 and 1759 for extra work. In 1760 a new clock made by John Davis was given to the church by the Her Grace the Duchess Dowager of Bolton and the next and last mention of Mr Muddle in the accounts was for a payment of £1 10s in 1764 for cleaning the church clock etc.[26] It was in 1750 while he was living at Southborough that Thomas, at the age of 42, was stated to be the father of the illegitimate daughter of Elizabeth Fry, who was then about 24 years old, that was baptised at Speldhurst, which is the village and parish immediately to the west of Southborough. Then when his father died in 1756, Thomas, who was sole executor of his father’s will, inherited the residue of his father’s personal estate. It was probably in about 1763, two years before he sold his house in Southborough, that Thomas moved back to Rotherfield because Thomas was one of the Overseers of the Poor of Rotherfield and described as a clocksmith of Rotherfield in an agreement for the maintenance of the poor dated 5 March 1764. In this agreement the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of Rotherfield agreed to pay John Dulake, a yeoman of Waldron, £245 to look after up to 50 poor people in Rotherfield Workhouse for a year starting on 5 April 1764, providing them with food, clothing, nursing etc. He was to also have the benefit from the work they were set to do. If the number in the Workhouse went above 50 he was to receive an additional two shillings per person per week for them.[27] When he was 62 years old Thomas married 44-year-old Elizabeth Fry, the mother of his illegitimate daughter, at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 12 February 1770. Elizabeth had been born at Speldhurst in 1726, but it has not been possible to tell which of the two Elizabeth Frys baptised at Speldhurst that year was the one who married Thomas Muddle. Thomas and Elizabeth lived at Rotherfield where they had two children born in 1770 and 1772.

Thomas was a clocksmith but he also owned farms that were occupied by tenants. The Rotherfield Rate Books record that in 1764 John Betts paid 9 shillings on land of Thomas Muddle at Maynard’s Gate valued at £4 10s. Then in 1771 an entry records Mr Muddle’s Maynard’s Gate Farm. In September 1772 William Towner paid 6 shillings for Mr Muddle’s Gardeners and Gamon Croft Farms valued at £4 10s. Then in 1775, 1776 & 1777 Thomas is named as the owner of Loose Farm. Thomas died at the age of 77, and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 16 February 1785; his burial record described him as a clocksmith. Thomas had made his will on 30 June 1781, four years before his death, when he described himself as a clockmaker of Rotherfield, and this will was proved by the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 12 May 1785. In this will Thomas made the following bequests: to wife Elizabeth all that messuage or cottage and garden and two pieces of assart land of Small Grove laying near Maynards Gate for her natural life, also the use of two thirds of my household goods and furniture for her natural life so long as she remain unmarried, and then to be equally divided between my son Thomas Muddle and daughter Mary Muddle; to Elizabeth Fry (my wife’s eldest daughter), who was also sole executrix of the will, all that one messuage or tenement and garden in Rotherfield upon Town Hill, also one third of my household goods and furniture; to daughter Mary Muddle all that messuage or tenement and several pieces of customary land in Rotherfield with all that one piece of assart land (now divided into two) called Gammons Croft: all the rest and residue of my personal estate, which was valued at less than £100 at probate, to my son Thomas Muddle.[28] Thirty-three years after her husband's death Elizabeth was living in the adjacent parish of Mayfield in Sussex when she died at the grand age of 92, and was buried in the Churchyard of St Dunstan in Mayfield on 1 March 1818.

Edward Muddle (1709-1788) clockmaker at Chatham

Edward Muddle was the second of the three sons of Rotherfield clockmaker and whitesmith Thomas Muddle and his wife Mary Dadswell; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex, and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 16 May 1709. Edward, like his two brothers, would have been trained as a clockmaker by his father, who was a master clocksmith and whitesmith at Rotherfield, and though he probably completed his apprenticeship in 1730 at the normal age of 21, it seems likely he continued working with his father at Rotherfield for about the next ten years while his younger brother was being trained as a clockmaker. When his maternal grandfather, Edward Dadswell, died in 1736 Edward, at the age of 27, inherited £5.[29] It was probably in about 1740 that Edward moved to Chatham in Kent where he set himself up in business as a master clockmaker. Then when he was 34 years old Edward married Elizabeth Hack at the Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin in Chatham on 18 September 1743. They lived at Chatham where they had eight children born between 1744 and 1758, four of whom died young. The Poll Book for the election held at Maidstone on 1 & 2 May 1754 for two Members of Parliament to represent Kent, records that one of the voters was Edward Muddle (spelt Micddle) of Chatham who held freehold property, consisting of a house and land, at Biddenden that was occupied by Thomas Borman.

When his father died in March 1756 Edward inherited £10. An indenture dated the 16 November 1756 records the purchase for £70 by Edward Muddle, clockmaker of Chatham, of property at Slicketts Hill in Chatham, abutting the highway leading to Upbury on the north, land of Robert Hills on the west, land called Pound Field belonging to the Dean and Chapter of Rochester on the south and John Holden’s land on the east, formerly occupied by John Taylor and William Musgrave and now by Olliff and Little, consisting of two messuages or tenements with washhouse, house of office, backsides, gardens and ground thereto belonging, from Kendrick Rogers labourer of Woolwich and his wife Elizabeth, and Thomas Judd husbandman of Shorne and his wife Mary. Another document, a bond for quiet enjoyment, also dated the 16 November 1756 bound Kendrick Rogers and Thomas Judd for the sum of £140 to be paid to Edward Muddle if their wives should later claim right of dower on these two properties.[30] A Gentleman’s spindle watch made by Edward Muddle, dated to about 1755, was sold in Germany in 2001, and Edward was described as being a watchmaker of Chatham when, by an indenture dated 29 September 1761, he was paid £16 to take William Roberts as an apprentice for a term of 7 years from 17 August 1761, out of which Edward paid 8s in stamp duty on 27 October 1761.[31] The Strood Churchwarden’s Account Book records that in 1764 they paid Mr Muddle 10 shillings for repairing their church clock.[32] Edward was described as being a coachmaker (which is assumed to be an error for clockmaker) of Chatham, when, by an indenture dated 30 December 1766, he was paid £20 to take Thomas Robins as an apprentice for a term of 7 years, out of which Edward paid 10s in stamp duty on 16 February 1767.[33] This Thomas Robins later became a master watchmaker at Chatham.

Elizabeth died in 1770 and she was buried in the Churchyard of St Mary the Virgin at Chatham on 17 May 1770. In 1771 Edward was given the job of replacing the old square faced clock on the Rochester Butcher’s Market Building (later the Corn Exchange) with a round faced one. Then two years after Elizabeth’s death Edward, at the age of 63, married 64-year-old spinster Margaret Toke at the Parish Church of St Bartholomew in Burwash, Sussex on 27 October 1772 by licence. Margaret was the daughter of George and Elizabeth Toke; she had been born at Ashford in Kent and baptised at the Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin in Ashford on 18 March 1708. She later moved to Burwash with her parents and some of her siblings. Her parents, brother John and sister Elizabeth were all buried in the Churchyard of St Bartholomew in Burwash. After her marriage Margaret would have lived with Edward at Chatham for five years until she died at the age of 69 and was buried with other members of her family in the Churchyard of St Bartholomew in Burwash on 10 February 1778. In a 1772 act of parliament entitled An Act for the better Paving, Cleansing, Lighting and Watching, the Streets and Lanes in the Town and Parish of Chatham, in the County of Kent, and for removing and preventing Nuisances and Annoyances therein, appointed 36 men, including Edward Muddle, who were proprietors and owners of houses or inhabitants of Chatham, to be Commissioners for putting this Act into Execution. The Daily Advertiser of 14 July 1775 reported that one of a number of valuable articles stolen from Dr Yonker's at Great Saffron Hill in London was a double cased silver watch numbered 208 made at Chatham by Muddle. This theft was also reported in the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser of 14 July 1775. Then the 19 February 1777 edition of The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury reported that three silver watches had been stolen from Isaac Heron's shop, one being a silver watch of poor sort made by Edward Muddle of Chatham numbered 497, for the return of which a reward of $4 was offered with another $8 for discovery of the thief.

On 4 January 1774 Edward took out a fire insurance policy with Sun Fire Office of London. This policy described Edward as a clock and watchmaker of the High Street in Chatham and the policy was for £300 to cover his dwelling house and adjoining washhouse constructed of brick with a tiled roof, and also £100 for two private tenements under one roof at the upper end of Nags Head Lane, St Margaret’s, Rochester then in the tenure of Tist and Shaw and constructed of timber with a tiled roof.[34] Then on 9 December 1777 Edward took out another a fire insurance policy with Sun Fire Office of London. This policy described Edward as a watchmaker of Chatham and the policy was for six things: First for £100 to cover Edward’s household goods in his dwelling house; Second for £150 to cover four private houses adjoining Slickolds Hill (probably Slicketts Hill) in Chatham in the tenure of Plummer and others, constructed of timber with a tile roof; Third for £100 to cover two private houses adjoining Gads Hill in Gillingham in the tenure of Coote and others, constructed of timber with a tile roof; Fourth for £250 to cover two private houses in King Street, Chatham in the tenure of Mears and others, constructed of brick with a tiled roof; Fifth for £100 to cover one house on Smithfield Bank in Chatham in the tenure of Stubbs, constructed of brick with a tiled roof; Sixth for £100 to cover three private houses behind the last in the tenure of Whitfield and others, constructed of timber with a tiled roof. This policy was for a total of £800 for which Edward initially paid £1 and then £1 0s 5d at Christmas 1778.[35] These insurance policies indicate that Edward must have prospered as a clockmaker and invested his profits in a number of properties in the Chatham area. In the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 18 December 1779 Edward was described as being a watchmaker of Chatham in Kent. A number of longcase clocks inscribed ‘Edward Muddle, Chatham’ have been offered for sale at auction, confirming that Edward was a maker of both clocks and watches.

When his spinster sister Elizabeth Muddle died, Edward, who was her sole executor, was described, in her will dated 18 December 1779 and proved 19 January 1780, as being a watchmaker of Chatham, and he inherited her copyhold property at Rotherfield together with any other real estate and the residue of her personal estate that consisted of money or securities for money. Edward had moved back to Rotherfield by the time he made his own will at the beginning of 1783, when he described himself as a gentleman. Presumably he had sold his clock making business at Chatham, and retired to Rotherfield to live as a gentleman. Edward died at Rotherfield when just on 79 years old, and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 10 April 1788. Edward’s will dated 20 January 1783 and proved at London by the Prerogative Court of Canterbury on 16 September 1790, made the following bequests: to his daughter Hannah the wife of John Walker, sugar refiner of Hackney, £300; to Sarah Landen the youngest daughter of Noble and Mary Landen, £300, to be paid when she reached the age of 24, or if she died before that it was to go to his sole executor who was his son Edward Muddle, gentleman of London, who inherited all the remainder of his real and personal estate.[36]

Nicholas Muddle (1716-1807) clockmaker at Lindfield & then Tonbridge

Nicholas Muddle who was born at Rotherfield in Sussex, and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 21 June 1716. Nicholas, like his two brothers, would have been trained as a clockmaker by his father, who was a master clocksmith and whitesmith at Rotherfield, and though he probably completed his apprenticeship in 1737 at the normal age of 21, it seems likely he continued working with his father at Rotherfield for a few years before moving to Lindfield in Sussex, which is about 14 miles west of Rotherfield, where he set up in business as a master clockmaker. Several longcase clocks have survived from the time Nicholas was at Lindfield; they are inscribed 'Nich. Muddle Lindfield' and have been offered for sale at auctions. When he was 27 years old Nicholas married Mary Durrant, who was about 21, at the Parish Church of All Saints in Lindfield on 25 January 1744. They initially lived at Lindfield where they had three daughters born in 1746, 1747 and 1749, the second of whom died when only eleven months old. During March 1746 Nicholas Muddle was paid 6 shillings by the Overseers of the Poor of Lindfield for a bill he had submitted; it’s not known what the bill was for, but possibly the Workhouse had a clock that Nicholas had repaired.[37] In the Window and House Tax assessment for Lindfield of 1747 Nicholas was record as having 9 lights in his house, and as this was below the 10 lights at which payment for individual windows was required he paid just the basic 2 shillings House Tax.[38] It was probably in 1752 that Nicholas and Mary moved to Tonbridge in Kent where they had four more daughters born between 1753 and 1762. The Tonbridge Overseers’ Accounts record Nicholas Muddle being assessed each year from 1753 to 1762 on a property in Church Lane with a yearly rental value of £3, and the yearly Poor Rate that Nicholas had to pay the Overseers on this property varied between 7s 6d and 13s 6d. The assessment for this property in 1763 was recorded as being for the occupier of late Muddles in the Church Lane with a yearly rental value of £3.[39] Church Lane, where Nicholas lived and presumably had his clock making business, is a short road running from Tonbridge High Street to the entrance of the Parish Church of St Peter & St Paul, whose Churchwardens paid Nicholas Muddle 1s 6d in 1758 as per his bill, but what this was for was not specified. When his father died in 1756 Nicholas inherited £10. While he was living in Tonbridge Nicholas made watches because the 14 July 1775 edition of The Public Advertiser carried a notice from the Public Office, Bow Street, London requesting that the office be contacted by the owners of a number of items, including an old silver watch inscribed 'Nich. Muddle, Tunbridge, No. 4861', found in the possession of some suspicious persons then in custody and thought to have been stolen. From 1763 to 1797 Nicholas was not recorded as being assessed for the Poor Rate in the Tonbridge Overseers’ Accounts so was he now living outside the parish but still had his business in the parish because the Churchwardens’ Accounts of Tonbridge Parish Church record that they made 24 payments to Nicholas Muddle between the years 1766 and 1786; these payments being mostly for cleaning the church clock but also included repairing the clock and chimes, repairing the lock on the church door and repairing candlesticks, the sums involved being anything between 1s and 15s.[40] When the payments stop in 1786 Nicholas would have been 70 years old, so this was possibly when he retired. In 1797 Nicholas Muddle, at the age of 81, was recorded as an inhabitant of Tonbridge Town who was liable to serve on juries.[41] Then from 1798 to 1807 the Tonbridge Overseers’ Accounts again record Nicholas Muddle as being assessed for the Poor Rate, now on a property with a yearly rental value of £5 5s on which the yearly assessment Nicholas had to pay varied between 15s 9d and £1 11s 6d.[42] Mary died at Tonbridge at the age of 82, and she was buried in the Churchyard of St Peter & St Paul at Tonbridge on 3 May 1805. Two years later Nicholas died at Tonbridge, at the age of 91 (not 92 as given on his burial record), and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Peter & St Paul at Tonbridge on 27 December 1807.

Edward Dadswell (1659-1736) yeoman at Rotherfield

Edward Dadswell was the only son of Robert Doudswell and his second wife Mary Aynscombe; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 6 June 1659. When Edward was only just on four years old his mother died and then when he was 17 years old his father died. On his father's death Edward inherited the properties: 1) Three parcels of land containing 6 acres 3¾ roods of assert of Crowborough at Linters between Droveford and Slingly, and held by a yearly rent of 18d. 2) A messuage and four parcels of assert of Crowborough containing 13 acres laying on the south of the highway leading from Doddshill to Crowborough and held by a yearly rent of 3s 3d. 3) The northeast end of a messuage that was formerly Philip Alchorne's and consisted of a lower room and an upper room above it upon Townhill in Rotherfield together with a little parcel of garden adjoining the said rooms lately divided from the garden of Philip Alchorne and 20ft in length, and held by a yearly rent of 3d. 4) A messuage with garden and the backside to the same belonging situated in Rotherfield town and occupied by Edmund Halfknight, adjoined the Town Mead on the east, the messuage formerly Stephen Farmer's deceased on the south, the messuage formerly Abraham Alchorne's on the north and the highway on the west, and held by a yearly rent of 6d. 5) The parcel of land of 5 acres near Horsegrove in Rotherfield together with the messuage and barn built thereon, and held by a yearly rent of 15d. 6) One piece of copyhold land called Droveford containing 6 acres of assert of Crowborough lying in Rotherfield, and held by a yearly rent of 18d. 7) Three parcels of assert of Crowborough called Marleings Field. 8) Two crofts of land containing 4 acres in Rotherfield, and held by a yearly rent of 15d. Edward was admitted as tenant of these properties at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 1 February 1677.[43] Three months later, when he was just on 18 years, old Edward married 27-year-old Elizabeth Elliott at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 4 May 1677. They lived at Rotherfield where they had nine children born between 1678 and 1692. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 12 January 1681 Edward sold to Thomas Muddle and his heirs two of the properties that he had inherited from his father. These properties were: the northeast end of a messuage that was formerly Philip Alchorne's and consisted of a lower room and an upper room above it upon Townhill in Rotherfield together with a little parcel of garden adjoining the said rooms lately divided from the garden of Philip Alchorne and 20ft in length, and held by a yearly rent of 3d; and a parcel of land of 5 acres near Horsegrove in Rotherfield together with the messuage and barn built thereon, and held by a yearly rent of 15d.[44] When Elizabeth's father, John Elliott, died in early 1681 his will left a fifth share of the bulk of his estate to Elizabeth, part of which was to be paid only after her mother died in 1700. The will stipulated that the executors were to use the money due to Elizabeth to purchase lands and tenements with clear title that they were to settle on Elizabeth for her life and then on her death they were to pass to Elizabeth's children as the executors saw fit. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 19 October 1681 Edward sold another of the properties he had inherited from his father. This time he sold to John Lockier and his heirs the messuage with garden and the backside to the same belonging situated upon Townhill in Rotherfield, formerly occupied by Edmund Halfknight, and adjoined the Town Mead on the east, the messuage formerly of Stephen Farmer on the south, the messuage formerly of Abraham Alchorne on the north and the highway on the west, and held by a yearly rent of 6d. There was no Heriot due as the premises were assert of Townhill, and John Lockier was admitted as tenant on payment of a fine of 30s to the Lord of the Manor.[45] At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 2 October 1684 and 4 April 1690 Edward Dadswell was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[46] At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 28 July 1691 Edward Dadswell was one of many on a list of customary tenants of the manor that were in default and each one in mercy (fined) 6d. One of the obligations of customary tenants was to attend court and if they didn't they were liable to an amercement, effectively a fine, and put on a list for the beadle to go round and collect the amercement.[47] At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 8 August 1694 and 18 April 1700 Edward Dadswell was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[48] When Elizabeth's mother, Ann Elliott, died in 1700 her will left the £42 due on a loan that she had made to Elizabeth's husband on 26 December 1687 to the six, then surviving, children of Elizabeth's sister, Mary Gilbert. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 2 September 1702 John Turk senior and John Turk junior sell to Edward Dadswell, a yeoman of Rotherfield, his son Thomas Dadswell and their heirs, a toft, formerly a cottage and two pieces of copyhold land belonging to it containing 7 acres, called The Pyke, together with meadow, pasture and woodland called by the names of Bancroft, New Reed, Picklegg and Rowland Wood containing 12 acres. And Edward Dadswell was admitted as tenant on payment of a fine of £7 to the Lord of the Manor.[49] At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 8 July 1709 it was recorded that out of court on 27 June 1709 Thomas Cheesman sold to Edward Dadswell, his son David Dadswell and their heirs, a cottage and piece of land containing one acre that were part of the assert of Crowborough abutting the highway leading from Shornebrook to Dadshill on the east, the lands of Edward Dadswell called Pothurst on the south and west and the land of Thomas Ovenden on the north, and the first proclamation was made for them to come to court to be admitted. The second proclamation was made at the Court held on 12 July 1710 but still nobody came to court to be admitted. Then when the third proclamation was made at the Court held on 2 July 1711 Edward Dadswell and his son David came to court and were admitted as tenants of this property on payment of 4d to the Lord of the Manor for two reliefs. At this court Edward Dadswell was also sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[50] The probate copy of the 1710 will of his son Robert refers to Edward as my loving father Edward Dadswell of Rotherfield aforesaid Clocksmith Yeoman but the original will has my loving father Edward Dadswell of Rotherfield aforesaid Yeoman showing that underlining in probate copies of wills indicates a copying error, and as there is no other indication that Edward was involved in clock making that his occupation was that of yeoman farmer.[51] At the Courts of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 22 April 1715 and 6 April 1716 Edward Dadswell was sworn in as one of the homage (jury of tenants).[52] Edward and Elizabeth’s son Robert, who had married and had two young daughters, died in 1710, then in 1712 his widow married weaver Joseph Moon. When Joseph and Mary Moon were expecting their first child Mary’s youngest child from her first marriage, 8-year-old Elizabeth Dadswell, became a charge on Rotherfield Parish. Because at the Sussex Quarter Sessions held at Lewes on 17 & 18 January 1717 the court ordered that Edward Dadswell and Joseph Moon were to pay towards the relief of Elizabeth Dadswell, a poor girl now chargeable to Rotherfield Parish, such allowance as the next session to be held shall think fit, unless they appear at that session to show good cause why they shouldn’t pay. Presumably Joseph Moon must have appeared at the next session held at Lewes on 2 & 3 May 1717 because the court then ordered that it was Elizabeth’s grandfather Edward Dadswell who was to pay the maintenance to the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of Rotherfield, which was £2 11s 4d for the money they had already expended and henceforth 12d per week. Presumably Edward had not appeared at this session but appeared at the next session held at Lewes on 18 & 19 July 1717 to appeal against the earlier order, but the court found that Edward was a man of good ability to pay the maintenance of his granddaughter and ordered that henceforth he was, at his own charge, to maintain and keep his granddaughter Elizabeth Dadswell until the court should think fit to order the contrary.[53] At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 2 April 1719 Edward Dadswell was sworn in as one of the homage as both a free and a customary tenant.[54] At the same Court Edward Dadswell and his son Thomas sell the property that they had purchased in 1702 to John Cripps junior, a yeoman of Speldhurst, who was possibly Edward Dadswell's nephew, son of Edward's sister Mary. This property was now described as a toft, formerly a cottage and two pieces of copyhold land belonging to it containing 7 acres, called The Pyke that has now also had a barn built on it, together with meadow, pasture and woodland called by the names of Bancroft, New Reed, Picklegg and Rowland Wood containing 12 acres. And John Cripps was admitted as tenant on payment of a fine of £9 to the Lord of the Manor.[55] At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 22 April 1720 Edward Dadswell senior was sworn in as one of the homage as both a free and a customary tenant. Then at the Court held on 29 March 1722 Edward Dadswell was again sworn in as one of the homage.[56] Elizabeth died at the age of 86, and she was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 11 July 1735. Edward died the following year at the age of 77, and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 12 August 1736. Edward’s will, which he had made on 7 June 1723 and in which he described himself as a yeoman of Rotherfield, was proved by the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 13 August 1736. In this will Edward left his farm of 28 acres at Rotherfield called Newmans and a woodland of 4 acres belonging to this property to his son Nicholas. This land was charged with paying an annuity of 40 shillings per year to his wife, but as she had died before Edward this no longer applied. To his son Thomas he left his property at Boarshead in Rotherfield Parish called Homestall, except the orchard and land called Forestall, leaving about 13 acres, and charged this land with paying his grandson Edward Muddle a bequest of £5. To his son Alexander he left his home at Rotherfield called Aynscombes of 15 acres, and also a woodland of 2 acres that belonged to Newmans Farm but adjoined Aynscombes, and also the orchard and land called Forestall at the Boarshead. He also made Alexander sole executor of his will and left him any residue of his personal estate after his debts had been paid.[57] It is difficult to tie up Edward's descriptions of his property in his will with the descriptions of his properties as detailed in the manorial court books. But as Edward was recorded as being a tenant of both freehold and copyhold property in the Manor of Rotherfield, and it was only copyhold property transactions that were recorded in the court books, at least some of the property in his will was probably his freehold property.

Thomas Dadswell (1688-1753) clockmaker at Burwash

Thomas Dadswell was the youngest son of Rotherfield yeoman Edward Dadswell and his wife Elizabeth Elliott; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 3 October 1688. Thomas is thought to have been an apprentice of his brother-in-law Thomas Muddle, who was a clockmaker at Rotherfield. He would probably start his apprenticeship in 1702 when he was 14 years old as this was the normal age to start an apprenticeship. It was also in 1702 that Thomas' father purchased property at Rotherfield that was to be for Thomas. This was recorded at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 2 September 1702 when John Turk senior and John Turk junior sell to Edward Dadswell, a yeoman of Rotherfield, his son Thomas Dadswell and their heirs, a toft, formerly a cottage and two pieces of copyhold land belonging to it containing 7 acres, called The Pyke, together with meadow, pasture and woodland called by the names of Bancroft, New Reed, Picklegg and Rowland Wood containing 12 acres. And Edward Dadswell was admitted as tenant on payment of a fine of £7 to the Lord of the Manor.[58] Thomas would probably have completed his apprenticeship in 1709 when he was 21 years old, this being the normal age at which to complete an apprenticeship. It seems that Thomas then remained at Rotherfield for several years presumably working for Thomas Muddle as a journeyman clockmaker. Because at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 9 May 1717 Thomas Dadswell was recorded as being the Deputy Beadle with his brother-in-law Thomas Muddle being Beadle.[59] Then when Thomas was 30 years old it was recorded at the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 2 April 1719 that Thomas Dadswell and his father Edward Dadswell sell the property that they had purchased in 1702 to John Cripps junior, a yeoman of Speldhurst, who was possibly Edward Dadswell's nephew, son of Edward's sister Mary. This property was now described as a toft, formerly a cottage and two pieces of copyhold land belonging to it containing 7 acres, called The Pyke that has now also had a barn built on it, together with meadow, pasture and woodland called by the names of Bancroft, New Reed, Picklegg and Rowland Wood containing 12 acres. And John Cripps was admitted as tenant on payment of a fine of £9 to the Lord of the Manor.[60] It was probably around this time that Thomas left Rotherfield and started his own clock making business at Burwash in Sussex, and it was probably the proceeds from the sale of the property at Rotherfield that gave Thomas the funds to setup his business. The Poll Book for the election held at Chichester on 9 & 10 May 1734 for two Members of Parliament to represent Sussex, records that one of the voters was Thomas Dadswell who held freehold property at Burwash and also resided there. Thomas was a clocksmith at Burwash when, by an indenture dated 29 July 1735, he was paid £2 10s to take his nephew Thomas Dadswell, son of his brother Edward, as an apprentice for a term of 7 years from the date of the indenture, out of which Thomas paid 1s 3d in stamp duty on 4 August 1735.[61] It’s thought that Thomas also took his nephew John Dadswell, son of his brother Alexander, as an apprentice as this John later became a clockmaker at Burwash. Thomas married Mary, though no record of their marriage has been found. They never had any children. When his father died in 1736 Thomas inherited his father’s property at Boarshead in Rotherfield Parish called Homestall, except the orchard and land called Forestall, leaving about 13 acres. Thomas died at the age of 64, and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Bartholomew in Burwash on 27 November 1752. He had made his will on 18 November 1752, just before he died, and this will was proved by the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 28 November 1752. In this will Thomas made the following bequests: to his brother Edward 5 shillings; to brother Alexander the rents of his property in Rotherfield Parish for his natural life, the property to then pass to Alexander’s children as tenants in common; to his brother David the rents of his property at Burwash for his natural life, except that his wife was to have use of the parlour and parlour chamber for the rest of her life, and after David’s death the property was to go to the children of his brother Nicholas as tenants in common.[62]

John Dadswell (1727-1789) clockmaker at Burwash

John Dadswell was the fourth child of Rotherfield yeoman Alexander Dadswell and his wife Anne Baker; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 1 October 1727. It’s thought that John was probably an apprentice to his uncle Thomas Dadswell, who had a clock making business at Burwash in Sussex, and afterwards continued working as a clockmaker in his uncle’s business. Then when his uncle died in 1752 John’s father inherited the household goods, tools and movables at Burwash, and John’s uncle David Dadswell inherited the premises at Burwash. It’s assumed that John then continued to operate the clock making business at Burwash, probably having raised money with a bond that was guaranteed by his father. Then when John’s father died in mid-1766 all the household goods, tools and movables he possessed at Burwash, which he had inherited from his brother Thomas, were inherited by John, subject to him paying off the bond that his father had guaranteed.[63] Then seven months after his father’s death John, at the age of 39, married Elizabeth Stevens at the Parish Church of St Bartholomew in Burwash on 14 December 1766. There were no children from this marriage. John was still a clockmaker at Burwash when he was paid £20 to take John Usherwood as an apprentice for 7 years by an indenture dated 18 August 1770, and out of this John paid £1 stamp duty on 6 November 1770.[64] This John Usherwood later became a clockmaker at Ticehurst. It’s thought that when John’s cousin Thomas Dadswell, who was a clockmaker at East Grinstead, died in 1769 that John may have taken his son Edward as an apprentice and that after Edward had completed his apprenticeship he continued to work for John at Burwash until he set up in business for himself at Eastbourne in about 1783. John would have continued making clocks at Burwash until he died, at the age of 62, and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Bartholomew in Burwash on 4 November 1789. Nine years later Elizabeth died and she was buried in the Churchyard of St Bartholomew in Burwash on 7 June 1797.

Thomas Dadswell (1719-1769) clockmaker at Rotherfield & then East Grinstead

Thomas Dadswell was the sixth child of Rotherfield yeoman Edward Dadswell and his wife Elizabeth; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 30 March 1719. Then on 29 July 1735, when he was 16 years old, Thomas was apprenticed for 7 years to his uncle Thomas Dadswell, who was a clockmaker of Burwash, for which his father paid his uncle £2 10s.[65] Thomas would have completed his apprenticeship in 1742 and sometime after this he returned to Rotherfield where he set up his own clock making business. When he was 29 years old Thomas married Mary Taylor at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 11 April 1748, and they had seven children born between 1749 and 1762. They first lived at Rotherfield where their first five children were born between 1749 and 1756 and where Thomas continued his clock making business. Then in about 1757 they moved to East Grinstead in Sussex where their last two children were born in 1759 and 1762, and where Thomas continued to work as a clockmaker until his death. Thomas’ brother-in-law William Hoadley had been maintaining and cleaning Cowden Church clock until his death in April 1763, and then in July 1763 the Cowden Churchwardens’ Accounts record a payment of three shillings for altering the clock being made to Hoadley, which was then crossed out and replaced by Dodsell, which is thought to be a reference to this Thomas Dadswell.[66] Thomas died at the age of 49 (possibly he was just 50), and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Swithun at East Grinstead on 12 January 1769. Mary died four years later, and she was buried in the Churchyard of St Swithun at East Grinstead on 13 September 1773. When his sister, Hannah Alchorne, died in 1802 Thomas’ children each inherited from her an equal share from a sixth share of the residue of her estate.

Thomas Dadswell (1749-1794) clockmaker at East Grinstead

Thomas Dadswell was the eldest son of Rotherfield clockmaker Thomas Dadswell and his wife Mary Taylor; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 30 March 1749. Then in about 1757 Thomas moved with his parents to East Grinstead in Sussex where he would have served an apprenticeship in his father’s clock making business until his father’s death in early 1769 when Thomas was nearly 20 years old. Though he would not have fully completed his apprenticeship Thomas must have taken over his father’s clock making business at East Grinstead and possibly also the training of his younger brother Edward, who would have only just started his apprenticeship with their father. Two and a half years after his father’s death Thomas, at the age of 22, married Sarah Holman at the Parish Church of St Swithun in East Grinstead on 13 October 1771. They lived at East Grinstead where they had eleven children born between 1772 and 1794, the first two of whom were twins. In 1773 the Churchwardens’ Accounts for Cowden in Kent record a payment of five shillings to Thomas Dodsell for cleaning the church clock, this being the same clock that his father had been paid three shillings to alter in 1763.[67] Thomas continued making clocks at East Grinstead and the Sussex Urban Business Directory of 1791-2 listed Thomas Dadswell as being a clocksmith of East Grinstead. Thomas died at the age of 45, and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Swithun at East Grinstead on 2 August 1794. Thirty-two years later Sarah died at the age of 74, at Sackville College in East Grinstead, which was an almshouse, and she was buried in the Churchyard of St Swithun at East Grinstead on 13 June 1826.

Edward Dadswell (1754-1802) clockmaker at Eastbourne

Edward Dadswell was the second son of Rotherfield clockmaker Thomas Dadswell and his wife Mary Taylor; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 9 June 1754. Then in about 1757 Edward moved with his parents to East Grinstead in Sussex where he would have started serving an apprenticeship in his father’s clock making business, but his father’s death in early 1769 meant that he either completed his apprenticeship working for his elder brother Thomas, who had taken on their father’s clock making business, or, as seems more likely from the later locations of his marriage and children’s baptisms, that he completed his apprenticeship working for his father’s cousin John Dadswell, who had a clock making business at Burwash in Sussex. Edward probably completed his apprenticeship in 1775 when he was 21 years old and for a few years probably continued to work for John Dadswell at Burwash because when he was 23 years old Edward married Ann Carter at the Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin in Battle, Sussex on 2 November 1777. They had eight children; the first was born at Rotherfield in 1778, the next two at Burwash in 1779 and 1782, and the other five at Eastbourne between 1784 and 1795. So it seems likely that Edward set up his clock making business at Eastbourne in about 1783. He then continued to make clocks at Eastbourne for the next 19 years until his death at Eastbourne, at the age of 48, and his burial at Eastbourne on 23 June 1802. Ann and at least some of her children are thought to have then moved to Hartfield in Sussex, where, 25 years after her husband’s death, Ann died at the age of 73, and was buried in the Churchyard of St Mary at Hartfield on 6 April 1827.

Thomas Hoadley (1650?-1720) blacksmith at Rotherfield

Thomas Hoadley married Jane Martin at the Parish Church of St Michael & All Angels in Withyham, Sussex on 27 April 1674. They were both then living at Rotherfield in Sussex. After their marriage they lived in the Boarshead area of Rotherfield Parish where Thomas worked as a blacksmith and where they had three children, all sons, born in 1676, 1679 and 1686. It’s thought that Thomas probably purchased a lantern clock that has the maker’s name ‘Tho Muddle, Rotherfield’ finely inscribed on the dial and that Thomas added the cruder inscription ‘1685 W H’ above the dial to commemorate the birth of his youngest son, William Hoadley, who later went on to become a clockmaker. Thomas died after 46 years of marriage and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 18 August 1720. Thomas had made his will on 10 July 1719, just over a year before he died, when he described himself as an aged and infirm blacksmith of Boarshead in Rotherfield, and this will was proved by the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 6 September 1720. In this will Thomas bequeathed to his eldest son Thomas his messuage, barn and two pieces of land thereto belonging with the appurtenances now in the several occupations of himself and Robert Burr situate and being at Boarshead in Rotherfield, subject to Thomas paying his mother forty shillings per year during her natural life and letting her dwell without paying any rent in part of the messuage occupied by Robert Burr if she so desires. To his wife Jane he bequeathed his bed on which he then laid that was in the parlour chamber together with all things belonging to it for her natural life and after her death it was to go to his son William. He also bequeathed to his wife his best joined chest (wooden chest) that stands in the hall chamber together with all the linen therein. To his son John he bequeathed £10. To his son William he bequeathed his copyhold messuage, orchard and garden in Rotherfield Town, subject to William paying his mother twenty-five shillings per year during her natural life. William was also to have £12, one pair of hemp sheets, four flaxen napkins, one pair tow sheets, his father's newest vice, one of his biggest anvils, one sledge, one large hammer, two pairs of smith's tongs, all the tools William uses to do his fine work and the household stuff that had been his aunt Devenish's. To his daughter Adderton he gave one shilling and to his grandson Nicholas Adderton twenty shillings. To his granddaughter Ann Burgis he gave fifty shillings. To his son Thomas he gave all the rest of his working tools and all the rest of his personal estate was to be equally divided between his wife and his son Thomas. He made his son Thomas his sole executor, and he appointed yeomen John Lockyer the elder of Rotherfield and William Maynard of Withyham as the overseers of his will and gave them five shillings each.[68] Six years after her husband’s death Jane died and was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 26 December 1726.

William Hoadley (1686-1756) clockmaker at Rotherfield

William Hoadley was the third son of Rotherfield blacksmith Thomas Hoadley and his wife Jane Martin; he was born at Rotherfield in Sussex and baptised at the Parish Church of St Denys in Rotherfield on 30 January 1686. It’s thought that William was an apprentice to Thomas Muddle, who was a clockmaker at Rotherfield, probably starting his apprenticeship in about 1700 when he was 14 and ending it in about 1707 when he was 21. Catherine Pullein in her history of Rotherfield quotes a letter from Mr Herbert F Fritt of Jarvis Brook, in which he states that he has the 9 inches square dial, hand, and parts of the works of an old 30-hour one-handed grandfather clock by Hoadley, Rotherfield that he dates to about 1710. When his father died in 1720 William inherited his copyhold messuage, orchard and garden in Rotherfield Town, subject to William paying his mother twenty-five shillings per year during her natural life. William was also to have £12, one pair of hemp sheets, four flaxen napkins, one pair tow sheets, his father's newest vice, one of his biggest anvils, one sledge, one large hammer, two pairs of smith's tongs, all the tools William uses to do his fine work and the household stuff that had been his aunt Devenish's. His father's will also stated that William was to inherit his father's bed after his mother's death, which happened in 1726. The tools that William used to do his fine work presumably refers to the smaller tools he would use to make clocks rather than the larger tools normally used by a blacksmith. At the Court of the Manor of Rotherfield held on 23 April 1721 the death was presented of Thomas Hoadley who held the copyhold premises consisting of a messuage and garden on Townhill in Rotherfield, formerly that of John Alchorne and his wife Elizabeth, paying a yearly rent of 5d. For a Heriot a cow valued at 40s was seized for the Lord of the Manor, and his son William Hoadley, on producing a copy of his father's will, was admitted as tenant of these premises on payment of a fine of 25s to the Lord of the Manor.[69] When he was 38 years old William married Mary Swatland at the Parish Church of St Michael & All Angels in Withyham, Sussex on 30 January 1724 by certificate. They were both then living in Rotherfield Parish. They had three children born between 1726 and 1732; their first child was baptised at Rotherfield Church but the other two were baptised at Withyham Hamlet Church. When his eldest brother, Thomas Hoadley, died in 1734 William was made one of the trustees of his brother’s will charged with the bring up of his brother’s three young orphaned children using the proceeds from the estate bequeathed to the son. Catherine Pullein in her history of Rotherfield states that a 1921 edition of Our Homes and Gardens had a description of a clock with the inscription ‘Hoadley, Rotherfield’ on its face that was owned by a lady in Ditchling who desired to learn its date. Pullein replied to her that at a Court of Rotherfield Manor in 1739 William Hoadley of Rotherfield, clocksmith, was mentioned as being owed £20 by William Brooks, who gave as security a cottage and land at Crowborough. Possibly this was the copyhold property that William in his will left to his son. On 20 September 1751 a written agreement was made between William Hoadley of Rotherfield and the churchwardens of Cowden in Kent for William to supply a new clock for their church with brass wheels, and case hardened spindles and pinions, for the sum of £11, and for William to also have the old clock. The agreement also required that William, during his natural life, was to keep the clock in good repair and clean it for five shillings per year. Half the £11 was to be paid when the clock was installed and half six months later. The agreement was endorsed on the rear by William’s son, who signed as William Hoadly Junr, on 26 January 1753 to the effect that his father acknowledge that he had received the full £11 from the churchwardens. So it seems from this that William had probably installed the clock in mid-1752.[70] William died at the age of 70, and he was buried in the Churchyard of St Denys at Rotherfield on 13 January 1756. On his burial record William was described as a widower and as his wife was also not mentioned in his will she must have died before him, though no record of her burial has been found. William had made his will on 12 February 1755, about eleven months before his death, when he described himself as a clocksmith of Rotherfield, and this will was proved by the Archdeaconry of Lewes on 9 December 1756. In this will William bequeathed to his son William his copyhold messuage or tenement, barn, garden, orchard and twelve acres of land thereto belonging situate at Crowborough in Rotherfield Parish, and any other real estate he may own. To his daughter Mary the wife of John Pike Ovenden, a butcher of Rotherfield, he left £50. To his daughter Elizabeth Hoadley, a spinster, he left £50 together with a feather bed and all items belonging to it that now stands in the kitchen chamber, two pair of fine sheets, one pair of course sheets and one fine tablecloth. All the rest of his personal estate was to go to his son William who he made sole executor.[71]

William Hoadley (1729-1763) clockmaker at Rotherfield